Kaspi.kz (KSPI:NASDAQ) - the Definition of High Risk, High Reward

There is not another business in the world like Kaspi.kz. A 59% net income margin, 50% YOY growth, and one of the strongest moats in the world - all for 11x earnings. So what's the catch?

First things first, a warning. The following write-up is ~9300 words long, meaning it’ll probably take at least 40 minutes to read it all at a speed where you can actually absorb the info. This post basically exists for 3 groups of people - investors who are already looking at, or just starting looking at Kaspi (for whom I hope this post can save a good bit of time); people from value investing hedge funds who want to hire me (good idea if you ask me); and people with far too much time on their hands.

To all others, I apologise - future posts will be more digestible.

Intro

Many apps around the world claim to be, or are trying to be, super-apps, but only a handful really fit the bill - WeChat and Alipay (both Chinese), Grab and Gojek (Southeast Asia), MercadoLibre (LatAm) and Kaspi.

In my mind, there are two requirements for an app to be considered a super-app: it must provide a large range of everyday services - payments, messaging, ride hailing, marketplace, lending and food delivery are the most common; and it must have a high penetration rate in its core market.

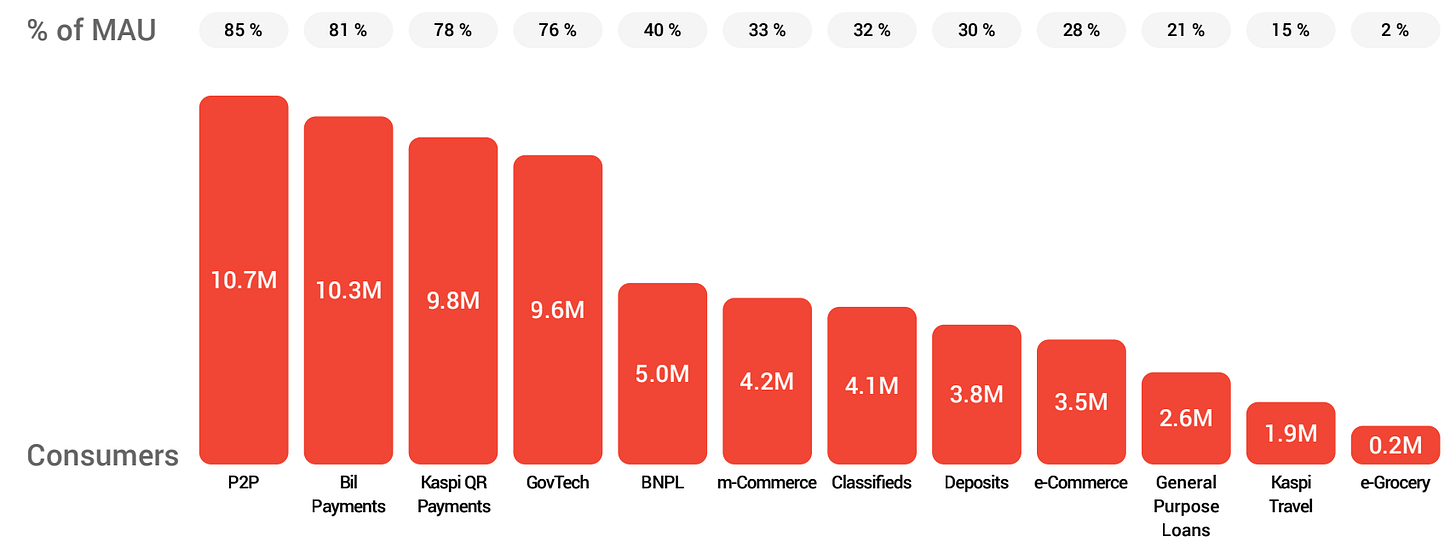

Kaspi certainly checks both of these boxes with their two-sided app. On the consumer side, their app includes P2P, in-store (QR), and bill payments; an amazon-style marketplace, classifieds, buy-now-pay-later (BNPL), general-purpose lending, a deposit account, e-groceries, government services, travel services and more. On the merchant side, it includes POS, financing, billing, B2B payments, delivery, advertising, tax services and more. Despite having only been launched in 2017, over 70% of their market’s population uses it each month, and >45% each day; it is arguably the most dominant super-app in the world (since WeChat faces competition from Alipay).

The quality of the business, combined with fantastic capital allocation and operational leanness, make for some quite outstanding financials - their 59% net income margin (on net revenue, after interest expense on deposits) is bested by only one company in the S&P500 (VICI, a REIT) and the asset-light nature of their business has allowed them to pay out more than half their earnings in dividends, even while growing at 40-50% a year (implying a 100%+ ROIIC). The 5.15% dividend yield alone would probably satisfy your average blue-chip dividend investor.

With a market cap of $25 billion, and Q4’23 earnings of $546m, the multiple is barely over 10.

At this point, I’m sure you must be thinking it all just sounds a little too good to be true. The market, while emotional at times, generally isn’t stupid. And you’d be right, there is a catch - if you hadn’t guessed from the company’s name, the country which they so thoroughly dominate is Kazakhstan, an autocratic oil nation with close ties to both Russia and China. You can understand why multiples may be a little lower there.

(Note - Kaspi has plans to expand across several more countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus. More on this later.)

In this piece, I will cover the business model, moat, growth potential and management in reasonable depth, and this is all pretty important stuff; but what really decides whether this investment will be successful is whether the political, economic and currency risks come to fruition - that is the section you should pay most heed to.

By the way, I want to give a big shout-out to Ilya Kan and his KIP Newsletter - he’s a value investor from Kazakhstan who has written a lot about Kaspi, and I would strongly recommend reading through his write-up on the business (and his other posts - his awareness of his own weaknesses and willingness to admit mistakes is incredibly refreshing).

The author of this article has a financial interest in the company mentioned. The views expressed are for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Business Model and Moat

Kaspi’s business is split into three main parts - payments, marketplace, and fintech, with net revenue split 33:31:36 and net income split 36:29:34. Each complements the others in such a way that Kaspi’s moat is far stronger than the sum of its parts, and customers are sort of forced to keep their money in their Kaspi wallet - the heart of the super-app ecosystem - and spend it via Kaspi products. All the while, Kaspi can collect net interest income on the wallet balance.

It’s hard to overstate just how much Kaspi has transformed life in Kazakhstan. In 2016, cashless payments in Kazakhstan constituted just 13% of total payment value1. In 2023, it was 86%2 (of which the vast majority is through Kaspi). That’s higher than the US, which is at 82%3. In Feb 2019, there were 137k POS devices in the country, with no Kaspi devices; 4 years later, there were 832k, of which ~60% were Kaspi’s. Marketplace is a similar story.

Payments

In 2023, the total revenue-generating payment value of Kaspi Payments was $62.5b (with fee-free payments being ~double this again) - average take rate for revenue-generating payments was 1.2%.

P2P

Kaspi’s most popular payment product is P2P payments, used by >90% of their MAUs; however, they don’t charge fees on transfers between Kaspi wallets (only to other banks), so P2P only makes up 7% of payment revenue. Despite this, it’s one of the most important parts of their ecosystem - if you’re anything but an elderly person in Kazakhstan, it’s considered strange (and a bit of a pain in the arse) if someone can’t transfer a couple thousand Tenge into your Kaspi wallet for dinner, which causes a strong social pressure to have the app among young and middle-aged people.

Kaspi QR & Kaspi Gold

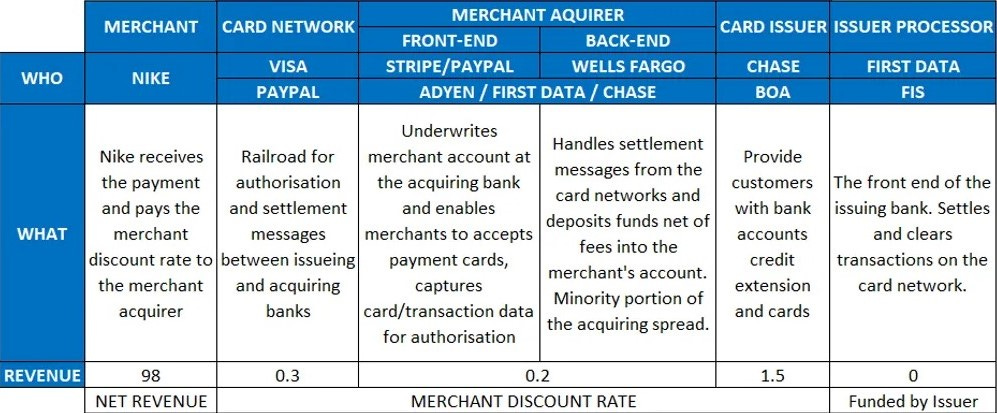

At the start of 2019, Kaspi had exactly a 0% market share of the in-store payments business - Kazakhstan was much like the US or UK, with Visa and Mastercard sharing a 96% market share. The payment system for these cards is actually pretty complex - the following illustration is ripped shamelessly from Atmos Invest's write-up on Ayden

But Kaspi wallets were already pretty popular for P2P payments, and management spotted an opportunity - if they could just provide a fast and simple terminal to merchants, they could sidestep this entire system and instead use the exact same technology as P2P payments to process in-store payments. This was what they created:

These devices allow payment in (at least) 3 different ways - the customer can hold their QR code up to the device’s scanner, then approve the payment; or they can scan the device’s QR code; or they can pay with a debit card like a normal POS device.

Instead of the 1.5-3.5% fee that’s typically taken when paying by card, QR payment would charge just 0.95% (or for card payment, 2.3%). Kaspi figured this difference would be enough to convince merchants to use them, and to convince their customers to pay by QR. They were right.

In 2019, Kaspi began sending these out for free to any merchant who wanted one - and by June 2020, the combined market share of Visa and Mastercard fell from 96% to 28%, while Kaspi’s rocketed to 66%. There aren’t many markets where the iron-grip of the Visa-Mastercard duopoly has been broken - to have done so in one year is an incredible testament to the network effects of Kaspi’s ecosystem.

Kaspi’s debit card, Kaspi Gold, has become one of the most popular cards in the country because of its integration into their ecosystem - for example, customers shopping on Kaspi marketplace have to either pay with BNPL or Kaspi Gold. QR payments and card payments together make up 71% of their payments revenue, and have a 75% market share, versus Visa at 19% and Mastercard at 4%.4

Bill Payments

The app can also be used to pay household bills, usually fee-free, a service used by 83% of the app’s users. These payments accounted for another 18% of payment revenue.

B2B

The remaining 4% comes from their B2B payments solution, which allows businesses all the way up the value chain to invoice and pay each other. While currently only used by 13% of their merchants, payment value more than doubled from 2022 to 2023, and this is expected to become a much more significant component of payments within the next few years.

GovTech

Finally, Kaspi’s “GovTech” is used by around 80% of MAUs to pay taxes and fines, receive social security, pay for public services fee-free, upload government documents, register their car, renew a drivers license, register a business and so on. Kaspi is now used to register the majority of cars in the country, and is being used to set up the majority of small businesses. While this segment generates no revenue, it’s yet another service that the people of Kazakhstan just love - it attracts people to the app and keeps them there.

Competition in Payments

The POS payment industry boasts the potential for one of the strongest moats in the world, as a two-sided network. The more customers use a certain payment system, the more sense it makes for merchants to offer that payment method and the less sense it makes to offer any others. Similarly, the more merchants offer a certain payment method, the more sense it makes for a customer to use it, and the less sense it makes for the customer to bother setting up any others. For this reason, Visa and Mastercard have had very little trouble in most markets holding their duopoly despite raising fees higher and higher over the years. Kaspi’s moat is likely even harder to breach, being monopolistic rather than a duopoly, and offering much lower rates (so less incentive to switch).

Other areas, such as P2P, don’t have such strong network effects in isolation. If you were going to send $500 to a friend, and your bank/payment service charged 2%, you might be very tempted to just download a separate fee-free app and suggest he/she do the same - especially if you know you’re likely to make more payments back and forth in the future. For that reason, Kaspi can’t really charge a fee on P2P, but they can still reap economic benefits from it - consumers keep more money sitting in their Kaspi wallet, allowing Kaspi to lend it out or put it in short-term treasuries with a healthy spread.

Competitors have been largely unsuccessful at challenging Kaspi’s payments empire. For example, back in May 2022, Ilya Kan wrote in the aforementioned write-up that “Onay, a national bus-card company, has started turning its popular Onay application and bus cards into a payments platform. They already have millions of users on its platform (every person using bus as transportation uses Onay) and have a history of successful product implementation”. Today, the “Pay” section of Onay’s website simply reads “Stay tuned for updates and pay attention to ONAY stickers”5 - I don’t know if they’ve given up or if they just move very slowly, but either way they don’t seem to pose much of a threat.

Marketplace

Kaspi’s marketplace is similar to Amazon, AliExpress or Mercado Libre. Around 60,000 merchants currently list their products on the site, paying an average 10% fee in exchange for advertising, free shipping, and access to Kaspi’s 4.8 million marketplace customers. These merchants are estimated to generate over a third of their revenue from Kaspi marketplace, on average.

With Kaspi advertising, merchants can pay to have their products (i) shown higher on search results, (ii) shown in a “suggested” section, or (iii) placed on banner ads. This offering is fairly new, having been introduced sometime in late 2022/early 2023 as far as I can tell, and is currently only used by ~6% of their merchants; but this should grow and contribute healthily to take rate.

All-in-all, marketplace was Kaspi’s fastest growing segment in 2023, with revenue up 87% YOY.

M-commerce

Unlike Amazon, Ali or ML, however, Kaspi marketplace doesn’t actually generate the majority of its revenues from e-commerce. 56% of marketplace revenues came from “m-commerce”, which refers to customers finding an item on the marketplace, then going to the physical store to inspect the item and complete the purchase in-person with Kaspi QR. The average take rate for m-commerce is 9%.

E-commerce

For e-commerce (take rate 11.5%), Kaspi enlists an army of third-party delivery companies to do the grunt work, but provides all the software required to make the logistics run smoothly, allowing them to maintain high margins and returns on capital without sacrificing much of the profit - the marketplace’s 55% net income margin makes Amazon’s 5% and Mercado’s 7% look abysmal, and reflects their excellent logistics. 51% of orders arrive in <2 days, which might sound bad compared to Amazon, but remember that Kazakhstan’s 20 million people are spread over one of the largest countries on Earth - here it is in comparison to continental Europe:

This percentage is also gradually increasing over time.

An important component of this efficient delivery network is their ‘Postomats’. Recognising the significant costs incurred by failed deliveries and last mile delivery in general, Kaspi began placing QR-operated parcel lockers in supermarkets and other convenient areas.

Customers can order straight to the Postomat from the marketplace; or if they order to their home but aren’t in to collect the delivery, the courier can place the package in the nearest Postomat. This has significantly reduced last-mile and failed delivery costs, and is “hugely popular with consumers” - 39% of marketplace deliveries were to Postomats in 2023. There are currently 6000 installed, and they plan to install another thousand in 2024.

Kaspi Travel

Kaspi Travel is one of their more recent products, launched in late 2020. It offers third-party flights, rail tickets, and most recently package holidays, and is now the largest online travel business in the country. The take rate for this section was 4.6% in Q4’23, but this is gradually climbing as packages (9% take rate) become a larger share of their sales.

E-Grocery

In 2021, Kaspi entered into a joint-venture with Magnum, Kazakhstan’s largest supermarket chain, to provide an e-Grocery service in the country’s major cities. Magnum would operate the ‘dark stores’ (think Amazon fulfilment centre, but for food), order SKUs and deliver groceries same-day; Kaspi would define the assortment and pricing, run personalised ads, and expose the service to their massive user-base.

Writing in May ‘22, Ilya discussed his doubts for the idea. “Mom-and-pop grocery/ convenience stores are scattered all across major cities and are, in a way, ingrained into local culture [ … ] Magnum doesn’t have the scale or the product quality to separate itself from these stores”. Almost two years later, it appears he may have been too pessimistic - in Almaty, where e-Grocery was first launched, 10% of the city’s 1.7 million-strong population used the service in Q4’23 (up from 6% in Q1), generating revenue for Kaspi of $31m. 92% of customers already rate the shopping experience as “excellent”. What’s perhaps even more impressive is that the store reached EBITDA profitability in just 5 months; Kaspi’s net income margin is now 6% in Almaty, and growing fast as the business scales.

Classifieds

If being the Amazon of Kazakhstan wasn’t enough, Kaspi are also determined to be the Craigslist/Ebay of Central Asia with their entry into the classifieds market.

This process began in 2019 with the acquisitions of three classifieds companies in Azerbaijan - turbo.az (cars), bina.az (real estate) and tap.az (general). Then in late 2022, Kaspi Classifieds (general) was launched in partnership with Kolesa, a leading classifieds in Kazakhstan which Kaspi’s CEO, Mikhail Lomtadze, already had an 11% interest in. Roughly a year later in the fourth quarter of 2023, Kaspi acquired a 40% stake in Kolesa, effectively giving them a controlling interest when considering Lomtadze’s stake.

Kolesa owns Kazakhstan’s no. 1 car classifieds site, kolesa.kz (13x better known than the next biggest) and Kazakhstan’s no. 1 real estate classifieds site, krisha.kz (4.6x better known than the next biggest). They also own the leading car classifieds in Uzbekistan, avtoelon.uz, which will provide a nice foothold for Kaspi to begin understanding the Uzbek market better, if they want to expand the super-app there.

Between the three sites, Kolesa generated $13.3m of earnings in H1’23, with the top-line growing of 300% YOY - this makes Kaspi’s purchase price of $88.5m (valuing the business at $222m) incredibly attractive. I’ll get a little more into why this may have been possible later, in the management section.

Going forward, Kolesa’s financials will be consolidated into Kaspi’s.

1P Car Marketplace

In the Q4’23 presentation, Kaspi briefly mentioned that they have just launched a first-party car marketplace in Kazakhstan - details and initial results will be shared in the Q1’24 update.

Juma

Twice a year, for 3 days, Kaspi cuts all marketplace fees to zero for its much-anticipated “nationwide shopping festival”, Juma. As self-congratulatory as that title may sound, it’s not much of an exaggeration - those three days in July 2023 (I can’t find November 2023’s results) saw $674m in goods be sold through the platform, a full 7% of the year’s total, as merchants drop prices and spend hard on ads.

According to Kaspi, the event is “loved by consumers and merchants alike”, and in 2024 they plan on hosting 3 Jumas instead of 2 for the first time ever. While they don’t charge any sellers fees during this period, it still generates a lot of revenue for them via BNPL, advertising and in-store payments.

Competition in Marketplace

Fundamentally, marketplace is certainly not as strong moat-wise as payments - it lacks a strong network effect, as merchants will happily list their catalogue on multiple marketplaces, and customers aren’t usually opposed to shopping around online for lower prices either. Still, Amazon manages to be completely dominant in the US, and Kaspi marketplace sells >10x more than its biggest competitor, so what gives?

The key here is logistics and economies of scale (Postomats help too). No one can match Amazon’s network of warehouses, fulfilment centres and couriers, which allow them to offer next-day delivery on the majority of products at a low cost to the merchant (somehow I can order a pack of pens for £2, receive them the next day, and somehow both the merchant and Amazon (presumably) turn a profit). This has put Amazon in such a dominant position that most customers don’t even bother to shop around anymore on small purchases - it’s unlikely you’ll find something for a lower price anywhere else, and even if you eventually manage to, it probably wasn’t worth your time.

This moat is probably a little stronger for Amazon, with their low-single-digit margin, than it is for Kaspi marketplace, which turns a 67% pre-tax margin - if we assume costs would be 50% higher for a competitor, they could theoretically still break even with half of Kaspi’s take rate. This does beg the question of why Kaspi have managed to become and remain so dominant.

The next biggest marketplace is wildberries.kz, at about a tenth the size of Kaspi. It’s a Russian company, run by Russia’s first female self-made billionaire, and has been immensely successful in many ex-Soviet countries. But after speaking to several people from Kazakhstan, the consensus seems to be that Kaspi and Wildberries aren’t really fighting for the same market. The selling points of Kaspi’s marketplace are convenience, speed, and quality, and it sells near enough anything you can think of. Wildberries, on the other hand, is all about value. You can score some bargains on there that you probably couldn’t on Kaspi, but wait times are measured in weeks/months and there’s a solid chance it’s a scam. It’s a similar story to Amazon versus AliExpress in Western markets. Additionally, Wildberries is quite heavily focused on clothes.

Fintech (Banking)

Kaspi’s fintech segment uses consumer and merchant deposits and wallet balances to fund short-term, high-yielding loans. 46% of loans are BNPL, generated primarily through marketplace purchases; 36% are general purpose consumer loans; 15% are merchant financing; and the remaining 3% is auto loans (strong synergies with car classifieds and new 1P car marketplace). The average yield of this segment, defined as interest income + banking fees divided by net loans, was 26.6% in 2022, reflecting the high-risk nature of these loans. The loan portfolio totalled $9.3b, against $12b of deposits, $3b in securities and $1.8b in cash - I’ll talk more about their financial risk later on.

Their “cost of risk” (loan loss provision divided by gross loans) has sat consistently at about 2% - a level that would usually make me slightly uncomfortable in a normal bank, but considering the 26.6% yield, it’s actually surprisingly good.

There are two keys to Kaspi’s relatively strong credit quality:

Buy now, pay later - these loans are low-risk, short duration and small ticket. What’s more, Kaspi can rapidly scale or scale back their BNPL loan portfolio in response to macroeconomic and behavioural changes - for example, in early 2022, they were able to quickly reduce originations as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine spiked oil prices and pushed inflation up to multi-decade highs, then quickly scale back up as it became clear consumer credit quality wasn’t badly affected.

Data - Kaspi has access to an abundance of data on the 14 million people that use the app - they know what they bought and when, how many people they sent money back and forth with using P2P, and so on. Imagine a consumer applies for a loan, but Kaspi can see the amount they spend on gambling has doubled in the past month - they can refuse that loan with data that regular banks would never have had access to. The same is true for the many merchants that sell on Kaspi marketplace, pay with Kaspi B2B and keep their deposits in a Kaspi account - Kaspi may even have a better idea of their financial health than they do. And it’s not just on an individual basis - Kaspi will be one of the first parties that knows about changes in consumer or merchant behaviour thanks to their dominance of payments, and they can tighten or loosen credit in real-time in response.

Kaspi also seems to have tighter credit requirements on consumer loans than many other Kazakh banks - I’ve read in several places things along the lines of “A Kaspi loan is 40-50% interest rate for me, Halyk or [other bank] offers 20-30%”.

Also, when a customer does default, you can imagine they would waste any time paying Kaspi back if possible, given what a dominant force the company is in the lives of Kazakhstan citizens (this is especially important given Kazakhstan’s credit scoring system remains a long way behind FICO and the likes, which would usually provide the required pressure). Because of this, Kaspi is able to eventually collect 97% of loans which go delinquent.

Once again, you can begin to see how all these business segments complement each other and make Kaspi’s ecosystem so much stronger than the sum of its parts.

The Other Moats

I’ve talked a lot already about the moats in each segment of Kaspi and the strength of the interplay between them; but I don’t think we’ve really gotten to the bottom of why Kaspi has been so successful already, and why I think they will continue to dominate in these areas and in the new areas they’re moving into. In my view, Kaspi’s two greatest strengths are - and try not to groan - their intellectual capital and their culture. Let me explain.

Intellectual Capital

Kaspi is by far and away the most sought-after employer in Kazakhstan. The acceptance rate on their graduate programme in 2021 was just 2% - approximately the same as Apple - and Kaspi carries the same prestige in Central Asia that Apple or Google do in the US. Everyone wants to work at Kaspi, and that means they get the best of the best from Central Asia’s top universities (as well as many people who, like Kaspi’s CEO Lomtadze, head to the US/Europe to attend university then return home).

Kaspi’s selection process is probably a little different too. Lomtadze explains it in greater depth somewhere in this hour long video, but in essence they don’t just want people with coding and mathematics skills - they want extremely motivated people who care about making good products. Anyone who has worked in software development can probably tell you that a small team of intelligent, hardworking devs can handily outperform a much larger team of devs who are just there for their paycheck - both in speed and quality.

This can be seen in their financials - technology & product development, sales & marketing and G&A summed to less than 10% of net revenue. Even if we generously assumed these to be entirely personnel costs, that’s far less than even Google, who spent ~20% of their 2023 revenue on staff by my estimate. I also think it can just be seen in the rate at which they’ve flawlessly introduced new features to the app. In the US, this advantage wouldn’t be so important - there are enough software engineers to go around. In Kazakhstan, it’s huge - no other domestic company can match their speed and agility in development.

Culture

This one might be a tougher sell, but it’s probably Kaspi’s single greatest asset. I could quote a hundred value investors on culture, but really there are three main points:

Culture has an enormous amount of momentum - turning a corporate culture around at a big company takes decades. The vast majority of fantastic cultures are built from the ground up.

It must come from the top. Management must embody the values they espouse.

It really does matter.

So, what’s Kaspi’s culture? In a nutshell, customer obsession.

In my opinion, that’s the best culture a company can have. Companies whose culture revolves singularly around better serving the customer again and again become not just successful businesses, but fantastic investments - Amazon, Costco, Interactive Brokers, Wise, Apple, and our very own Kaspi, to name a few.

But managements know this, and there are a hell of a lot more companies that claim to have this culture than actually do. How do we know Kaspi is in the latter category?

I think the biggest sign is their focus on net promoter score (NPS). For those that don’t know, NPS simply asks the question “on a scale of 0-10, how likely are you to recommend this to your family and friends?” - if they respond 0-6, they’re a ‘detractor’; 7 or 8 and they’re a ‘passive’; and 9-10 makes them a ‘promoter’. The score is calculated simply by subtracting the percentage of detractors from the percentage of promoters. According to AsiaMoney, product heads at Kaspi are not benchmarked on user growth, revenue or profit, but solely on NPS - a sort of ‘build it (well) and they will come’ mentality.

In 2012, Lomtadze had been with the bank for 5 years, and had successfully turned it from a corporate bank into a retail bank. They had just hit 1 million credit cards issued, making them Kazakhstan’s number one credit card leader. Then they put out an NPS survey on the product. When the score came back negative, Lomtadze claims it took just 48 hours to kill the product, which at the time accounted for 1/3rd of their entire revenue. “People hated different fees attached to credit cards and that they could not repay the debt over time, due to its revolving nature. A negative NPS meant for us that credit cards did not fulfil our mission.”

This culture drips down through the rest of the organisation. Lomtadze says employees come to work every day thinking about how they can make the everyday lives of Kazakhstanis better; when they design a product, they’re thinking about their parents, siblings and friends using it. This is evident in their overall NPS - back in the early 2010s, it was in the 40s; when they published their IPO prospectus in 2020, it was 87.3. That’s a pretty insane number - it means more than 87.3% of people answered 9 or 10 to how likely they were to recommend it. It’s hard to compete with that.

Growth Potential

Kaspi’s growth has been phenomenal - the top line’s 4-year CAGR is 38%, and this has somehow increased over time. But Kazakhstan’s economy just isn’t that big ($246b GDP, 2023) and Kaspi already serves about 70% of its 19.6 million inhabitants. One of the most common concerns I hear is, ‘how much room does Kaspi really have left to grow?’. While it’s true their user base can’t grow much further (maybe 10-15%), I think we can still see strong top-line growth within Kazakhstan - here’s why.

Payments

TPV is total (revenue-generating) payment value. This graph shows a clear trend - the longer a customer remains with Kaspi, the more they spend/send via Kaspi (and it’s a surprisingly linear relationship, too). If everyone reached the ~3.6m KZT/yr ($8050) of the 2018 cohort, that would roughly double payments revenue overall. Plus, the older cohorts don’t seem to be showing any sign of slowing - the cap may be much higher than that.

B2B payments is also a big opportunity, as their fastest growing segment of payments. In 2023 it made up 4% of payments revenue, despite being used by only 13% of merchants. If merchant volumes behave anything like consumer volumes over time, this could become a very significant component of payment revenue - maybe a quarter. And according to Kaspi, “B2B payments is just the start of a long list of innovative merchant services from us.”

Marketplace

E-commerce / m-commerce are only used by 34% / 33% of MAUs, and 11% / 59% of merchants respectively. So users could probably double from here, and usage per user can also grow significantly as more of the places where users shop start selling on Kaspi marketplace. Increases in merchant advertising, a service currently only used by 6% of Kaspi’s merchants, will also contribute substantially to revenue growth over the coming years.

Within travel, Kaspi estimate package holidays alone could be a $1b market, with a 9% take rate - that could probably push an additional $60m to the bottom line. There’s a lot of room left for growth in the rest of travel too.

E-grocery, Kaspi Classifieds, Kolesa and the 1P marketplace are all too hard to put any numbers on, but present substantial potential for further growth.

Fintech

BNPL and general-purpose loans are only used by 41% and 21% of their merchant base respectively, but I don’t think they’re bound to go much higher. BNPL will probably increase slightly as marketplace penetration increases. Car financing is in the process of transitioning from a standard retail banking product in which they have little edge, to something offered within their 1P and 3P car marketplaces - as a result, car financing has dropped from 8% of loans in Q1’22 to only 3% in Q4’23, but I expect this to reverse direction now they’ve gained control of kolesa.kz and opened their own 1P marketplace. Penetration of online car finance is currently just 0.3%.

On the merchant side, the penetration of merchant and micro-business financing has increased from 21% to 25% over 2023, and should continue growing over time.

Deposits are growing faster than loans, with the deposit user base up 27% versus loans’ up 12%, and total deposits up 43% versus 32% for loans. Only 35% of users currently use Kaspi Deposits, so there is a lot of room for growth here. This should allow for continual expansion into new areas of lending. Kaspi has guided for 20% fintech revenue growth in 2024 - I would guess all in all, there’s maybe 60-100% growth remaining in Kazakhstan (in their current lending areas).

All in all, this suggests there’s probably 100-150% growth left in Kazakhstan with the core businesses. Newer services, especially classifieds and an expanding suite of business services, may be able to further increase this. But what about other countries?

International Expansion

Kaspi has been saying for a fair few years now that they plan to expand across Central Asia and the Caucasus “in the medium-term”, with the long-term goal of serving 100 million people. I’m guessing the Russia-Ukraine war and the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War (Armenia-Azerbaijan) threw a spanner in the works, but now that things have somewhat stabilised I suspect it won’t be too long until we see them beginning their expansion.

These regions are characterised by high levels of cash usage, limited digital payments infrastructure, low e-commerce penetration and low consumer debt - an ideal environment for Kaspi to dominate. So how large is the international opportunity?

In Central Asia at least, not that big. Even if we include Mongolia and Afghanistan, Kazakhstan still makes up slightly more than half the GDP of the entire region:

From this list, Uzbekistan seems like the most likely first target. While a lot poorer than Kazakhstan, their population is substantially larger, and their GDP is big enough that this expansion could justify the investment. They are also reasonably similar politically to Kazakhstan, whereas Turkmenistan is much more authoritarian. Also, Kolesa’s avtoelon.uz should allow Kaspi to begin understanding the political, economic and cultural dynamics from afar, and makes a good starting point from which to expand their offering in the country.

But if they can win the approval of Turkmenistan’s government, that may also be an attractive target.

In the Caucasus, Azerbaijan is the obvious choice. With a GDP of $79b (2022) and population of 10 million, it’s no small fry; and Kaspi has a clear route in through the three classifieds businesses they already own in the country. Thinking a little further out, Azerbaijan could provide a path into the remainder of the Caucasus (Georgia - $25b, Armenia - $20b) and possible even Turkey. Given that Kaspi have stated their goal as serving 100 million people, and Turkey alone has 85 million, it obviously isn’t in their plans at the moment - but with a GDP just over $900b, no currently operating super-apps and very high cash usage, it could be an incredibly lucrative market. Still, I won’t stake any hopes on it.

A country that seems to interest Kaspi’s management more is Ukraine. Shortly prior to the beginning of the war, Kaspi purchased Portmone group, a small Ukranian fintech offering P2P, bill and loan payments, among other things, for between $10-20m. By all accounts, this was basically just a license purchase to allow Kaspi to deploy their payment offering in the country.

“With its payments licenses and substantial merchant and bank relationships, the acquisition of Portmone will allow Kaspi.kz to enter the Ukrainian market. The combination of high cash usage, high smartphone penetration and a population of 42 million, means Ukraine offers a substantial, multi-year digital growth opportunity.” - Mikhail Lomtadze, CEO

It’s anyone’s guess when the war will end, and what Ukraine will look like at the end of it (if it even exists). But assuming Ukraine does survive, it will remain a very attractive market for Kaspi, with almost $200b GDP (pre-war) and relatively weak competition in payments, marketplace and consumer financing.

If Kaspi was to expand their main business into the three other markets in which they already have some kind of presence - Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Ukraine - the total GDP of their markets would increase by ~135% (using $160b for Ukraine).

So between growth within Kazakhstan and expansion internationally, I think it’s fair to say Kaspi’s profits still have a lot of potential upside from here.

Risks

I think it’s pretty obvious by now that risks aside, Kaspi is undervalued. A business with the moat, return on equity and growth story that Kaspi has simply doesn’t deserve to be trading at 10x earnings if things are to continue going swimmingly.

But as I’ve said in previous posts, you simply cannot value something without a good understanding of its risks, and this only becomes more important when investing in a country like Kazakhstan. Whether Kaspi’s risks come to fruition is what will make or break this investment - I’ll go through each in turn and explain why I’m comfortable with them.

Geopolitical Risk

Between the 23rd of February and the 3rd of March, 2022, the share price fell from $79 to $35, as Russia began its invasion of Ukraine. Just three months prior, the stock had peaked at above $140. Today, with no clear end in sight and Putin looking more unstable than ever, I think it’s fair to assume the market is still pricing in substantial geopolitical risk.

Kazakhstan is in the rather unusual position of having pretty good relations with Russia, China and the US. Russia unsurprisingly, seeing as they were the same country 33 years ago (fun fact - Kazakhstan, not Russia, was actually the last country to leave the USSR). Good relations with the US began in 1991 with the US being the first country to recognise their independence; a mutual interest in nuclear non-proliferation and Kazakhstan’s security have kept it going since then, alongside US investment in oil & gas operations in Kazakhstan. China is incentivised to maintain good relations with Kazakhstan due to its geographical importance in the belt and road initiative, being a large part of the path on which China aims to build road and rail links to Europe and Russia. China has also made large investments in Kazakhstan’s energy resources, including the purchase of Petrokazakhstan and construction of an oil pipeline between the two countries. In 2023, China displaced Russia as Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner.

Kazakhstan has been attempting to distance itself from Russia since the invasion of Ukraine, recognising the need not to be lumped in with Russia to maintain foreign direct investment (FDI) levels and avoid sanctions. In 2022, Kazakhstan refused to recognise the sovereignty of Donetsk and Luhansk, the Ukrainian regions which Russia used to justify their invasion. The EU has also acknowledged Kazakhstan’s efforts to ensure its territory is not used to circumvent sanctions against Russia.

But they’re treading a fine line - 94% of Kazakh oil exports go through or into Russia (80% through the Caspian Pipeline), and Kazakhstan is reliant on Russia for a range of food and chemical imports. If Kazakhstan strays too far from Russia, we could see oil flows through the Caspian Pipeline interrupted or cut off entirely (as has happened briefly several times already).

However, I don’t think investors need to fear an invasion, as some media outlets have suggested. For one thing, Putin has had fantasies for decades about Russia, Ukraine and Belarus being reunited under one nation, as they share a common ancestry in the Rus’ people (read more here). The same cannot be said for Kazakhstan. Also, China has pledged to support Kazakhstan in its “independence and sovereignty”, warning in a clear nod to Russia against interference. The Chinese government cancelled a major Sinopec investment in Russia in response to the CPC pipeline shutdowns.

Political Risk

Kazakhstan is an authoritarian presidential republic with a president as head of state, and a prime minister, elected by the president, as head of government. The prime minister serves a mostly technical role, with the president holding practically all the political power.

Nur-Sultan Nazarbayev was Kazakhstan’s president from the dissolution of the USSR until 2019, when he resigned and elected then-speaker of the house Tokayev in his place.

In early January 2022, peaceful protests began over the lifting of a fuel price cap, and within a few days spread nationwide in Kazakhstan, developing into violent riots over general dissatisfaction with the country’s government and economic inequality. On January 5th, Tokayev brought in Russian troops, giving them shoot-to-kill orders - at least 238 protestors were killed, and ~10,000 arrested. Kaspi’s share price fell from $115 to $82 within the day. Tokayev also used the events as an opportunity to consolidate power, ousting Nazarbayev and many of his loyalists from their remaining positions of power; though the Nazarbayev family still remains one of the country’s richest and most influential, after decades of siphoning.

In my mind, there are two principal political/legislative risks to consider. First - is there a chance that the Kazakh government forcibly taking over Kaspi given what a fundamental part of the Kazakh economy it has become?

I think not. Or at least it’s a very small chance. Tokayev has repeatedly laboured that attracting foreign investment is one of the main goals of his regime, and what worse way would there be to do that than by screwing over the shareholders of the largest publicly traded Kazakh company, one trading on the NASDAQ no less? Despite how I might feel about his character since the January 2022 unrest, Tokayev has shown himself to be diplomatically excellent, and I’m sure it’s obvious to him that it wouldn’t be a smart move.

The second concern is whether the Kazakh government could begin squeezing Kaspi harder for tax revenues.

To some extent, the same argument as before applies. While one could understand the desire to do so, as Kaspi has basically made itself just a tax on economic activity in Kazakhstan, the additional few hundred million dollars in annual tax revenue from singling out Kaspi probably wouldn’t be worth the reputational damage as an investing destination. An increase in the general corporate tax rate from its current 20% level may be more likely, but I think the economics of keeping it low, attracting more FDI, and using the proceeds to monetize oil and gas resources faster are superior. Plus, an increase to, say, 30% would only mean a 12.5% drop in profits, which isn’t make or break for my investment, so I’m comfortable with this risk.

Economic and Currency Risk

On a macro scale, Kazakhstan’s economy is characterised mainly by a large reliance on oil & gas exports. O&G constitutes 20-25% of GDP and 55-60% of exports, and funds 35% of fiscal revenue in a typical year. There’s a lot of nuance to Kazakhstan’s economic situation and its implications on Kaspi’s valuation, but this post is already stupidly long so here’s a summary of how I see the economic and currency risk of this investment:

Kazakhstan have enough oil to keep producing for a veeery long time; but if oil prices drop or Russia cut off the CPC for a longer period of time, their fiscal deficit (0-3% of GDP normally) could get a lot worse. That would mean either taking on debt (government debt is currently only 25% of GDP) or selling off some reserves (these currently total $36b, i.e. not that much). Either option could lead to currency depreciations and a spike in inflation.

Here’s a chart of USD/KZT over the last 10 years:

The good news is, it’s been reasonably stable (at least for a developing country with close ties to Russia) since the move to a floating exchange rate in 2015. I’m okay with gradual depreciation, as that just results in gradual inflation, and since Kaspi’s payments and marketplace earn a percentage fee, their revenue in USD isn’t really affected over the long term.

Spikes in inflation could be worse, potentially leading to reduced consumer spending and higher credit cost of risk. However, even as inflation hit a peak of 23% in Feb ‘23 (higher than was even reached in 2015, when the value of the Tenge halved in a few months), Kaspi’s consumer credit quality remained strong:

This makes me reasonably comfortable with Kazakhstan’s economic predicament.

Financial Risk

Kaspi probably receives some level of market discount due to the $12b of consumer deposits and $9b of consumer and SME loans on their balance sheet - I doubt the Kazakhstani consumer is seen as the most stable on the world stage.

The asset side I’m not too concerned about - their credit quality has historically been decent and more importantly consistent, even in the face of some fairly bad economic environments. And if things get a lot worse than they have been, e.g. due to a full cut-off of the Caspian Pipeline, they do have the ability to very quickly reduce their loan portfolio size - only ~22% of their financial assets have maturities more than a year away. They also hold $3b of debt securities, which are mostly Tenge-denominated Kazakh treasuries. Overall, their are very well capitalised, with a Tier 1 Capital to risk-weighted assets under Basel III of 17%.

But ever since the regional banking crisis in March 2023, I’ve been a lot more worried about banks’ deposit side and liquidity matching. Fortunately, Kaspi is pretty safe in this regard - firstly, 80% of their deposits are insured by the Kazakhstan Deposit Insurance Fund (KDIF), so there shouldn’t be any risk of those fleeing; and secondly, over 80% of their deposits are term deposits, with their demand deposits being easily covered by liquid assets. To use the banking term, Kaspi have a positive cumulative liquidity gap (assets exceed liabilities) up to any maturity.

Currency is also well matched - 90% of deposits and 100% of loans are KZT-denominated.

As an aside, Halyk Bank of Kazakhstan is trading at a sub-4 P/E, 18% dividend yield as I write this, even after moving from ~$10 in 2022 to $18. Could be an interesting one for ballsy bank investors - perhaps I’ll look into it and do a little write-up here at some point.

Other Red Flags

Kaspi Ownership

It being Kazakhstan, there are bound to be some slightly dodgy things going on behind the scenes - you can’t build a business as big as Kaspi without cosying up nicely to the Kazakh elites (as the company’s chairman, Vyacheslav Kim, has done very successfully).

One of the richest and most influential men in Kazakhstan is (was) ex-president Nazarbayev’s nephew, Kairat Satybaldy. In 2015, he acquired his initial position in Kaspi - by Dec 2017, he owned 30% of the business. However in June 2018, slightly over a year before Kaspi’s first attempt to IPO on the LSE, Satybaldy sold his entire stake on the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange (KASE). 8.5% was repurchased by Kaspi; the remaining 21.5% seems to have been purchased by Vyacheslav Kim, then transferred “for certain non-cash consideration” to Lomtadze.

One of Kazakhstan’s top elites owning a third of the business probably would have raised some red flags at the IPO. It has therefore been speculated that this transaction was purely for appearances, and behind the scenes Satybaldy may have had some kind of formal or informal agreement with Lomtadze wherein he could reclaim those shares at his discretion (read more in this Forbes article).

However, following the unrest in January 2022, Satybaldy was sentenced to 6 years in prison for fraud and embezzlement, and the Kazakh government is in the process of rendering his ‘illegally acquired’ assets to the state - so far, $1.5b has been reclaimed. It remains unclear whether his supposed phantom stake in Kaspi may be claimed by the state in the future; and if this did happen, whether it would be sold or used by the state to exert some influence over Kaspi’s decisions.

Kolesa Acquisition

Lomtadze first became involved with Kaspi in 2006 while working for the private equity firm Baring Vostok. The firm bought a 51% stake in Kaspi (then known as Bank Kaspiysky), which at the time was just a normal commercial bank, and when it ran into trouble in the GFC, Baring Vostok moved Lomtadze into the CEO position. From there, he removed most of the management team, replacing them with colleagues from Baring Vostok (this bit isn’t really dodgy - Kaspisky was close to failing at the time, and he clearly built a high-quality team).

Lomtadze has evidently maintained quite a close relationship with Baring Vostok - not just via their mutual share in Kaspi, but also other businesses such as Kolesa. When Kaspi acquired their 40% stake in Kolesa in 2023, it was Baring Vostok that they bought it from. What makes me somewhat suspicious about this deal is just the price they paid - the valuation of $222m meant they were paying just 8.3x earnings, based on H1’23 results. This was for a business whose revenue had just grown 302% YOY. I think the most likely explanation for this is that Baring Vostok, which invests mostly in Russian companies but has an American founder and likely a lot of non-Russian investors, desperately needed to monetize some assets to fund outflows after the Ukraine invasion - Kaspi was there willing to provide the liquidity, but basically held all the cards so was able to get a bargain price for the stake.

Still, the web of connections between related parties inevitably makes me slightly uncomfortable.

Management

The CEO, Mikhail Lomtadze, was born in Georgia and studied business at university in Tbilisi. Shortly after leaving, he started up an an accounting/audit/consulting firm, GCG Audit, with friends from university, which went on to become the largest consulting firm in Georgia and was bought out by Ernst & Young.

Finding himself at a bit of a loose end and with some money to throw around, he headed to the US to do an MBA at Harvard, graduating in 2002. That same year, he met Baring Vostok founder and CEO, Michael Calvey, and was so impressed by the man that he practically begged to be hired, saying “I don’t need any salary. I just want to work for Baring Vostok”6. This seemed to work - he was hired, and in 2004 became a partner.

As mentioned, Lomtadze was put in charge of Kaspi in 2007 as the bank was struggling through the unfolding GFC. He recalls “We basically fired everyone”, replacing executives with colleagues from BV, and began hiring tech-savvy graduates, rather than bankers. At the time, Kaspi was principally a commercial bank - retail constituted only about 5% of their business - but it was that 5% that he was interested in. I like this quote of his: “Each company has to know what its competitive advantage is, and continually invest in that competitive edge”. He saw that they had no moat in commercial banking; in retail however, technology could be their edge.

It took about 4 years for them to completely rotate the business from commercial to retail. A year later, in 2012, they were the second biggest retail bank in Kazakhstan, with more credit cards issued than any other. From there you pretty much know the story - they started building up the ecosystem, starting first with an e-wallet and bill payments, then introducing the marketplace, Kaspi Gold credit card, P2P payments, the two mobile apps, QR pay and so on, all with an unwavering focus on simplifying life for the customer.

In every interview I see with him, Lomtadze stresses the importance of surrounding yourself with the right people. When asked what he’d tell his 25 year-old self, he said “Choose the right people. At the age of 25, I didn't think that way and just acted on intuition. Now I can clearly say that it is the people around me that are the most important guarantee of success.” He is adamant that the management team he’s built has been and will continue to be the single biggest factor in their success - and not just in the way that every lousy CEO opens their shareholder letter “thank you to the hard work of our team, we couldn’t have done it without you”; he seems genuinely enamoured with them. Presenting at a fintech forum in 2022, he said “Our team is just – I mean it’s crazy, really. I gain so much pleasure everyday from the fact that I get to work with our members” (thanks again to Ilya Kan for the translation - read the full thing here).

Another thing that’s struck me is Lomtadze’s habit of setting clear strategic goals and actually following through. In far too many companies I look at, ever year the CEO will come out with a new strategic goal, “this year we want to expand our range of services”, “this year we want to refocus on our core business”, “this year we’re streamlining our business to produce cost savings”, meanwhile their revenue sits stagnant and profit oscillates about 0 (if I have to listen to one more CEO talk about their new go-to-market strategy…).

Not at Kaspi. In the 2020 letter, Lomtadze said their number one goal for 2021 was to accelerate adoption of Kaspi QR by consumers, and Kaspi Pay by merchants. A year later, QR payments were up 8x and 4.5 times as many merchants were using Kaspi Pay. For ‘22, he named continued merchant onboarding and greater penetration of merchant products, such as marketplace, as their main focuses. Merchant numbers doubled again YOY, and marketplace penetration rose from 50% to 65%. The top priority in 2023 was increasing their users’ average transactions per month - over the year this figure increased from 60 to 71. Another swing, another hit.

For his efforts, Lomtadze has now won PwC’s Kazakhstan CEO of the year for 5 years in a row.

All that is to say, the management seems pretty excellent to me. Capable, energetic, shareholder-oriented and extremely ambitious - the only thing I would like to see is a little more transparency, especially regarding Satybaldy’s stake, but such is the way of business in an oligarchy I suppose. I have faith that these guys will continue to find new ways to grow long into the future with new products, higher usage across products and potentially international expansion.

For any current or prospective Kaspi investors reading, I would strongly recommend listening to this lecture from Lomtadze to get a better idea of his personality.

Summary & Conclusion

In my mind, the holy trinity of value investing is high business quality, high management quality and low valuation. It’s exceedingly rare to find something which excels on all three points, but I believe Kaspi is one of those diamonds in the rough. To summarise:

Super-apps (much like diamonds) require a rather specific and uncommon of circumstances to come about. First, a market needs to be underserved in a range of services (payments, marketplace, consumer finance), with no apps having a large penetration of the markets already. Secondly, an ambitious and capable team must come along and not only create a clean, well-liked service for each of these needs, but also integrate them all into a single app and ecosystem before anyone else gets there (notice there are no true super-apps in highly developed markets - everyone already used Amazon for marketplace, Paypal for payments and so on). But like a diamond, once a successful super-app does come about, it’s exceedingly hard to damage. Businesses can and do compete with each of Kaspi’s offerings on an individual basis, but without the ecosystem and a massive userbase behind them, they will always be fighting an uphill battle. Creating an entire separate ecosystem also doesn’t seem to work - Halyk Bank and others have tried and largely failed. Altogether, Kaspi have one of the strongest moats I’ve come across to date. They also achieve excellent returns on capital (allowing them to pay out big dividends even as they grow), and have a significant growth runway ahead as detailed - the business quality box is well and truly checked.

I won’t bother repeating anything about management, as you’ve just read that bit. That box is clearly checked in my view.

Finally, valuation. In 2023, payments, marketplace and fintech earned $691m, $555m and $653m respectively, with management guiding for 25%, 40% and 15% net income growth for 2024. Overall, $1.90b last year and $2.39b this year.

The share price at the time of writing (April 1, 2024) is $131 (annoyingly about 10% higher than it was when I started writing this). With about 192 million shares outstanding, the market cap is $25.15b, or about 10.5x earnings. Even if profits stopped growing tomorrow, the stock yields a 5.15% dividend - a level that would probably satisfy your average blue-chip dividend investor. The valuation box is resoundingly checked.

Kaspi has had an excellent run in the last 2 months, up almost 50%. While it was certainly more attractive beforehand, I think the above reasoning demonstrates that Kaspi continues to represent excellent value at ~$130 per share.

For anyone that made it this far, well done. That was pretty dense. But if you found it useful, I really hope you’ll subscribe if you haven’t already, and perhaps share it with a fellow investor?

And if you have any questions at all, drop them in the comments below. I’ll get back to you shortly.

https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Conferences/2021/session-1-mikhail-lomtadze-presentation.ashx

https://tinyurl.com/u7zx8pvf

https://tinyurl.com/wh6zb4ed

https://nationalbank.kz/en/news/elektronnye-bankovskie-uslugi

https://onay.kz/#/pay

https://www.forbes.com/sites/daviddawkins/2020/11/25/the-two-billion-dollar-mystery-behind-the-ownership-of-london-listed-kazakh-fintech-kaspi/?sh=65a5db294a39

My understanding after talking to people from Kazakhstan is that without Kaspi life there would suck a lot.

High quality business led by a competent team, trading cheap.

Kazakhstan business environment is more developed than people realize regardless of the “stan” in the end, bordering Russia, being in the neighborhood of Iran and Afghanistan. It sounds more exotic than it is.

Great write up and incredibly interesting story. Your insight on underdeveloped economies trending toward superapps at the end makes a ton of sense to me and I had never thought about it from that perspective.

I don’t think I have the stomach for the geopolitical risks personally but this is an incredible write up.