Vistry Group (VTY.L) - A Classic Troubled Value Investment

Temporary cost problems, misinterpreted by the market as a fundamental issue, have left this high-quality growth company at less than 8x underlying earnings.

Executive Summary

Vistry is the UK’s largest developer of affordable housing, and is set to benefit from rapid growth in affordable and private rented developments under the recently-elected Labour government. Moreover, they operate a capital-light private-public partnerships model, which is high-ROCE, acyclical and protected by a strong moat. Management, despite some shortcomings, have shown themselves to be effective and reasonably shareholder-oriented. The stock has recently dropped by 45% due to short-term and likely non-recurring issues, which the market has fundamentally misunderstood, allowing the purchase of this business at an effective P/E multiple of just 7.4.

Changes to the Very Good Value Portfolio

Hingham Institution for Savings (HIFS) has appreciated from $170 at purchase to $290 today, including a 20% gain immediately following Trump’s election win. While I don’t disagree with the market’s assessment that a Trump presidency will be good for banks, I believe the conservative culture at HIFS means it will benefit less than other banks, and a 20% gain is not justified.

(Side note - betting platforms had a Trump win at a ~55% chance immediately before the election. Assuming market efficiency, that would imply the drop if Kamala had won would have been ~24%. In other words, the market was valuing HIFS at $190 for a Kamala win, versus $295 for a Trump win. To me, that is an insane differential.)

$300 was the approximate (conservative) fair value price I had in mind for HIFS. Consequently, tomorrow (14th November 2024), the HIFS shares will be sold and fully replaced with Vistry, resulting in a 29% allocation. If fundamentals do not change in a major way, I do not expect to sell shares below £15 (current price: £7.15).

Industry Overview

Vistry operates in the UK housebuilding industry. This is a rather complicated space, and it has taken me a couple of months to get my head around it (I’m still not sure I’m all the way there), but I will try to provide sufficient background to understand Vistry’s position. It is also surprisingly hard to find definitive figures for a lot of this stuff, so I apologise if any of the numbers are a bit off. The ones that matter should be right.

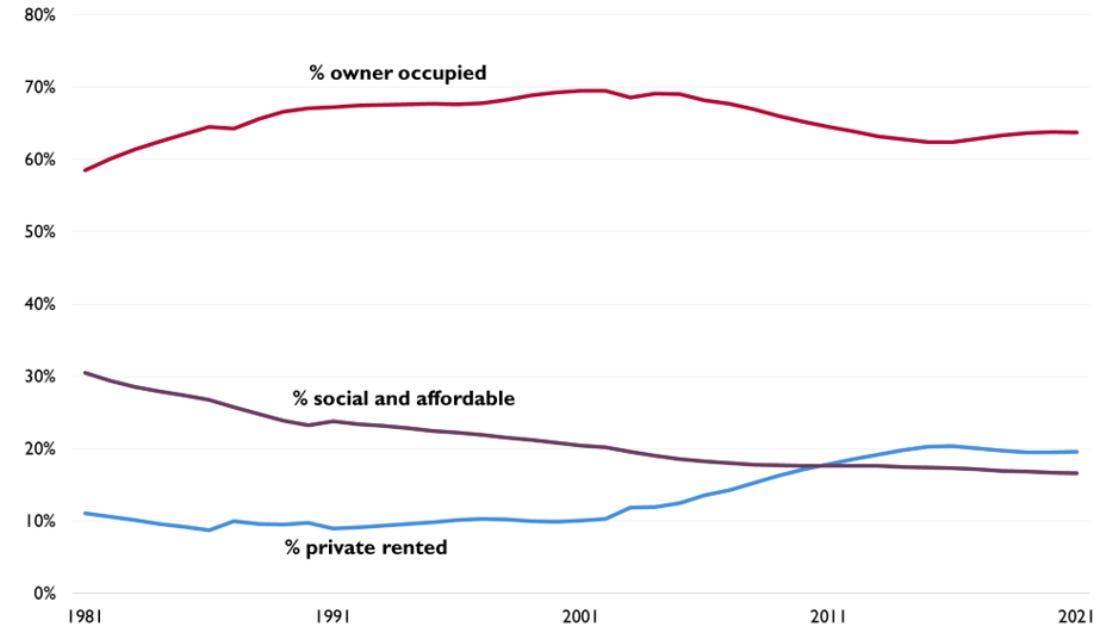

There are currently around 25.5 million dwellings in the UK. 63% of these are owner-occupied, 20% are rented from a private landlord at market rates, and 17% are occupied under an affordable housing scheme.

Affordable Housing

The 4 million homes in the UK that are classified as affordable housing are held under a fair few different tenures, with the most significant being:

Social rent - typically rented out at 50-60% of market rates, often to those on welfare benefits.

Affordable rent - capped at 80% of market rates.

Shared ownership - resident buys a portion of the house (generally 25-75%) at a discounted rate, then pays rent on the remaining portion, also at a discount to market rate. They may also gradually buy the remaining portion that they do not own over time.

This chart shows how the number of units delivered under each tenure has changed over time.

~80% of the affordable housing stock is owned by not-for-profit Housing Associations (HAs, a.k.a. Registered Providers). Another 15-20% is owned by local councils (known as Local Authorities, or LAs). About 1% is owned by for-profit registered providers (FPRPs), though this share is growing quickly.

Funding

Roughly half of England’s affordable housing is delivered or funded under a regulation called Section 106. S106 requires developers of private housing to contribute to housing-related needs in the area around a development - usually, this includes either building a certain number of affordable units into the development (often ~20%), or if this is not possible, contributing financially to affordable developments nearby.

The other half is funded by the government, primarily via Homes England’s Affordable Housing Programme (AHP).

Build-to-Rent

A growing segment of the market is build-to-rent (BtR), or as Vistry calls it, PRS (private rented sector). This refers to the construction of dwellings specifically for rental, rather than sale. Development is usually funded by an institutional investor - most often pension funds - which then holds the properties long-term, earning a steady 4-6% annual return.

The Planning Permissions System

A central part of the development of new housing in the UK is gaining planning permissions (often referred to simply as “planning”). Unlike the US, the UK doesn’t really have a zoning system - instead, permission to develop is granted on a case by case basis, with every request going through the Local Planning Authority (LPA), a division within the council.

It’s fairly universally agreed that the UK’s planning system is overly complex and needs reform - the process typically consists of several rounds of pre-application back-and-forth including S106 negotiations, followed by an official application, then consultation with the public, environmental groups and so on, then maybe to a planning committee before a final decision - which may then be appealed several times if it’s a ‘no’. The whole process can take from several months up to several years (though you wouldn’t know it from official statistics - I won’t get into why these are misleading), and NIMBY groups are often able to prevent the construction of desperately needed housing supply thanks to the public consultation.

The Traditional Housebuilding Model

Despite the name, housebuilders in the UK aren’t really in the business of housebuilding - or at least, this is not where they differentiate themselves.

Really, it’s all about land - developers build up a large bank of land, often 10+ years’ worth, and gradually work it through the planning system. Then once they get planning, they drip-feed units onto the market, being very careful not to build too fast and bring down prices. Construction itself is, of course, outsourced to contractors. The differentiation is in choosing the right plots, in minimising S106 commitments (a good relationship with the planning board helps here), and in reading the market to build and sell at the highest rate they can without affecting prices.

Because the units are built without a buyer lined up, this is referred to as the ‘speculative model’.

Here we see the breakdown of new builds. Self-build we haven’t covered, but it’s fairly self-explanatory. You may note that affordable is a higher proportion of new builds than existing stock, and yet its share of the housing stock is going down in the first chart. There are two reasons for this - first, housing which is sold (rather than rented) at a discount to market price is affordable in terms of the build model, but will subsequently be considered owner-occupied, rather than affordable stock. Second, the UK has a “Right to Buy” scheme where people in affordable housing can purchase their home from the HA or LA that owns it.

The Partnerships Model

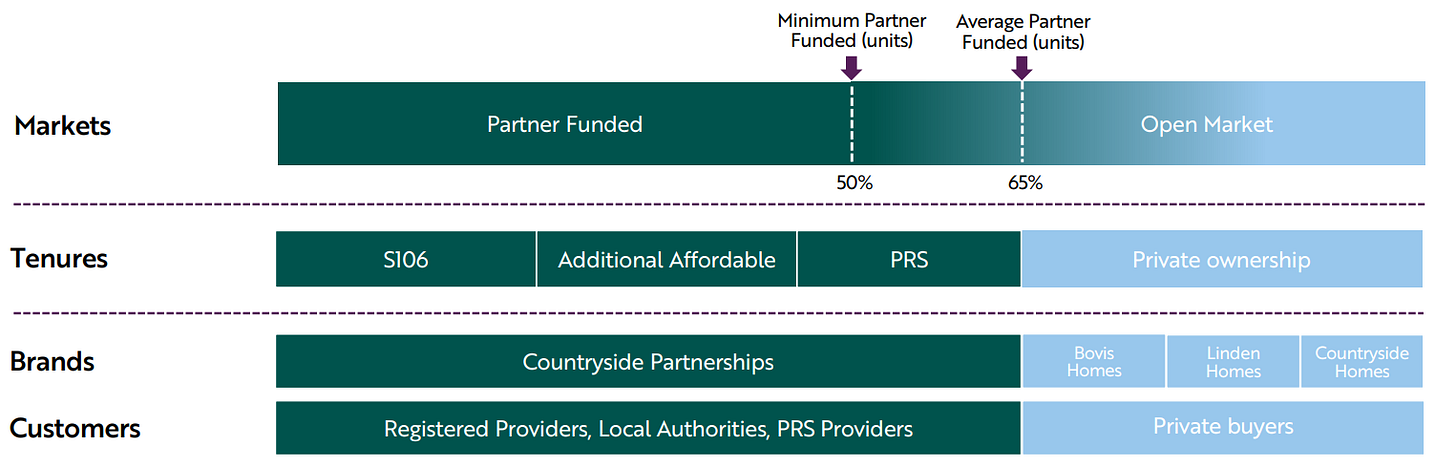

The partnerships model differs significantly from the speculative model employed by most housebuilders. It involves collaborating with housing associations, local authorities and PRS investors (collectively, ‘partners’), to deliver a mixture of affordable, PRS and private for-sale units.

The terms of these partnerships vary significantly project-to-project. In some cases, land will be provided by the developer, and a certain number of units allocated to partners (‘developer-led’). In other cases, a housing association, for example, may own some permissioned land and bring in the developer to build the units (‘partner-led’). In either case though, the partner will usually pre-pay for the units, before construction even starts. Additionally, there is often a variable component to the price tag such that certain costs are passed onto the partner, reducing the developer’s risk.

(For a more in-depth understanding of the partnerships model, this report from Grant Thornton may be helpful - particularly pages 6 and 8.)

Business Overview

Vistry has historically operated both a partnerships business and a traditional housebuilding business, but a year ago they began winding down the latter to go pure-play partnerships. (This transition is ongoing, but they no longer separately report results for the two units as the line between them has become blurred.)

On their partnerships projects, they aim to sell 65% of units to partners, and 35% into the private market (though on a project by project basis, the ratio may be anywhere between 50:50 and 100:0). You may wonder why they don’t just go fully partner-funded, but I think this is part of the beauty of the model - they can take on massive developments, with economies of scale on the labour side (labourers can go unit-to-unit with no downtime) and the cost of obtaining planning spread across many houses; while not running into the problem that big private developments face of oversaturating the market and taking 5+ years to sell all the units. Additionally, it aligns well with the inclination of LAs to have affordable units integrated in with private ones.

Vistry is not the only business that runs a partnerships model, but it is the largest by a wide margin. They’re expecting to deliver 18,000 homes in 2024, most of which will be partnerships. Other significant players include:

Keepmoat - 4,100 in 2023

Lovell - likely to do ~3000 in 2024

Berkeley - 3,900 in 2023, although their model is somewhat different

Because there’s a somewhat blurred line between traditional and housebuilding models, it’s difficult to put a number of Vistry’s market share, but I would estimate it’s approaching 50%. In mixed-tenure urban regenerations specifically, which can probably be described as Countryside’s specialty, it’s well in excess of that.

History

By name, Vistry was formed by the 2019 merger of Bovis Homes and the housing business of Galliford Try. The current CEO, Greg Fitzgerald, was CEO of Galliford between 2005 and 2015, a period over which they produced good results including a significant expansion of their partnerships business. He subsequently spent about a year as chairman, then in 2016 retired.

In 2017, Bovis Homes was not having a great time. They had expanded too quickly over the previous few years, and quality had suffered - their Home Builders Federation (HBF) rating had fallen from 5 stars to just 2. I think food safety ratings are probably the closest parallel to the HBF system - 5 stars is table stakes; 2 is just disastrous (and it won’t be long until the authorities come knocking). Fitzgerald, having built up a reputation as a talented operator while at Galliford, was brought out of retirement to rescue the company. Within 2 years, they were back at 5 stars, and shortly afterwards, they bought the aforementioned Galliford Try.

By form, however, it was really the 2022 merger with Countryside Partnerships that created the Vistry of today.

Countryside pre-covid was really the exemplar of what the mixed-tenure partnerships model can be. They were already the market leader, delivering 4400 homes in 2019 (versus Keepmoat’s 4000, Galliford Try’s 3300, Lovell’s 1140), and having the best reputation and track record. Moreover, their partnerships division (which constituted about half of their profit) achieved a ROCE of 78%, blowing the 15-25% typically achieved by UK housebuilders out of the water. However, the market seemed unwilling to recognise this quality, rewarding them with a sub-10 P/E multiple, lower than many peers (housebuilders, like banks, are often valued on a multiple of book value, rather than earnings, due to the importance of their land holdings - meaning the higher your ROE, the lower your P/E).

Consequently, Countryside’s brilliant then-CEO Ian Sutcliffe announced plans to split the business in two. Unfortunately, shortly afterwards, his wife was involved in a serious car accident, causing him to step away from the business. The man they chose to replace him was, in a word, worse. He started walking back the promise to split the business (why would a self-interested manager seek to split their empire in half?) - much to the annoyance of shareholders. This prompted Browning West, an activist value investor, to take a 10% stake, for which they received a seat on the board. The following year saw the resignation of the Chairman, CEO and CFO, and the announcement of a plan to go pure-play partnerships. However, Countryside was still unable to find a strong CEO candidate, and after several months, the board agreed to put the company up for sale. Finally, in September 2022, they agreed to a stock-for-stock merger with Vistry (the specifics of which I will discuss in the section on management).

Post-Merger Developments

Things have broadly gone rather well since the merger. Cost synergies in excess of management’s estimates were achieved, the stock more than doubled, and in September 2023, the company announced its plan to go pure-play partnerships.

Since then, they have been slowly winding down the non-partnerships business - finishing existing developments, transferring plots to the partnerships side where appropriate, and selling them off if not. All told, this wind-down is expected to release ~£1 billion of capital, which is to be returned to shareholders via buybacks and dividends, depending on price (around £200m has been returned to date).

However, on the 8th of October this year, it was announced that they had discovered cost understatements on a few of their sites totalling £115 million. The stock tumbled from £13 to £9.50. A month later it was announced they’d found another £50m of losses, and the stock fell further to £7.15 today. I will explain shortly why I believe the market has completely misunderstood the problem here. But first…

The Growth Story

England has seen about 200,000 new builds per annum in recent years, of which ~60,000 affordable. While that’s a big improvement from the 2010s, it’s still not enough. A 2018 estimate from the National Housing Federation put the need at 340,000 (of which 145,000 affordable), while other (somewhat less credible) estimates put it as high as 442,000.

The new Labour government has set the goal of 1.5 million homes over the next 5 years. The media have largely reported on this as a target of 300,000 homes per year, but this isn’t really accurate - given how long it will take to get the ball rolling, actually delivering 1.5 million would probably mean doing circa 400,000 in year 5.

People are right to be sceptical about that goal, especially after seeing how badly the Tories failed on their promise to deliver 300,000 homes per year by 2024. But I think 300,000 by 2028/9 (the last year of the current term) is not unrealistic. The attempts of the Conservatives over the last decade faced massive resistance from a voter base with many NIMBYs (“I support more affordable housing - just Not In My Back Yard!”), who opposed changes like freeing up some of the green belt or reducing the community consultation requirements. However, Labour voters are much more likely to be in need of affordable housing, and less likely to be NIMBYs, giving them the ability to push these changes through. Their enormous majority in the recent election also helps.

I think we’re already seeing Labour start to put their money where their mouth is. Changes so far include:

Changing local housing targets from an “advisory starting point” (thanks Gove) to mandatory, meaning LPAs will be obliged to design a housing plan that would meet these targets, and approve projects which meet this plan (else potentially face intervention from central government).

Changing the way those aforementioned housing targets are calculated, which should, in aggregate, raise them by ~21%.

Reallocating some of the protected green belt - primarily bit that have been developed before, or are surrounded by urban development as ‘grey belt’ land, which can be built on if at least 50% of the development’s units are affordable

Broadening the definition of brownfield land

Allocating an extra £500m to the current AHP budget.

And Greg Fitzgerald had this to say on the H1 call:

“So Labour in the run-up to the election talked a lot about housing. They could have said after winning the election, only joking, it's business as usual. What they haven't done is - they have absolutely - and I've never seen, and I've been doing this for 43 years, nothing like it, whether it's meetings, letters to local authorities, to housing associations, to us, they mean business. And you can all be skeptical, and there's an element - I'm a skeptical person. But the fact is, I think they mean business and I think they're going to do it.”

Obviously, Greg is not an uninterested party here, so take it with a pinch of salt - but it lines up well with the policy changes they’ve announced publicly.

Why Vistry Wins

The private market is not going to be able to drive much of this increase. Unlike affordable and PRS, where the main barriers are planning and funding/investment, the limiting factor in the open market is demand. Sure, reducing the cost associated with planning may encourage developers to accept slightly lower sales prices (as might the lower land costs for grey-belt areas), which would stimulate some more demand, but the effect is not going to be dramatic.

The majority of the increase is instead going to have to come from affordable and PRS. Even if private sales can grow 25% from the average of the past few years, affordable/PRS would have to double to make up the rest. That’s going to be a massive medium-term tailwind for Vistry. The grey-belt stuff is likely to favour them too, as the clear leader in majority-affordable projects.

It seems Homes England are well aware of how important Vistry will be here as well. Again, take with a pinch of salt, but Greg also said the following in the H1’24 meeting:

In the last 6 weeks, the most influential person in the affordable housing market met with one of our largest shareholders … but just as the shareholder was leaving the room, he [the other guy] said, "By the way, one other thing you can pass on to Vistry, what's all this about 22,000, 23,000 units by 2028? How are they going to do?". Be in no doubt, Mr. Shareholder, if the government are going to get anywhere near where they want to get to, we need and we'll be pushing very, very hard for Vistry to be doing 30,000 to 40,000 units per annum, not by 2028, a lot quicker than that.

That’s optimistic, but I could see Vistry’s completions making their way into the low-mid 30s by 2028 if the funding is there and the planning reform is successful. 32,000 units would represent a 15% growth rate from 2023-2028.

Economics and Moat

Return on Capital

The main appeal of the partnerships model is that it’s capital-light. There are two main reasons for this.

Partner-funded units are pre-sold, typically 1-2 years in advance. To illustrate the importance of this, let’s use a numeric example. Imagine you buy a plot of land for £50,000; it takes 3 years to work through design and the planning system, costing another £50,000; it then sits empty for 2 years as the plots before it are built and sold; then it takes 1 year to build the unit, at a cost of £150,000; and finally, it’s sold for £350,000. Your return on capital, despite an impressive margin, is only 13%.1

Now imagine you’re paid not when you sell it, but 18 months beforehand. And let’s say you drop the price down to £315,000 to compensate (the partnerships model does indeed run at a lower margin). Your ROC is now 18%2; and what’s more, the partner has gotten a good deal too - by paying 11% less, 1.5 years earlier, they’ve essentially earned a 6.6% return on their cash in those 18 months, a rate any pension fund will be pleased to earn risk-free. (Effectively, pre-selling arbitrages the difference in discount rates that you and the partner use, though that might be a bit of an esoteric explanation.)Houses don’t need to be drip-fed onto the market. Continuing with the above example, you can now take out that 2 years of waiting for the units before to be sold. Because you’re building all our houses at once now, let’s assume construction time rises from 12 to 18 months; and because house prices rise over time, let’s also say the sale price is instead £305,000. Despite these headwinds, your ROC has just jumped to 29%.3

Land is often provided, pre-permissioned, by the partner. In order to reflect the variety of arrangements Vistry runs, let’s say you now build a second house alongside it, except for this one, the buyer provides the land, planning in-place, and pays you £175k up-front for the construction (which still costs you £150k). Across the two projects, your ROC is now an astounding 49.4%4, despite the combined margin being halved versus the original scenario I laid out.

Vistry earned a 21% ROCE* in 2023, a down year for the housebuilding industry. This was better than competitors, who generally sat between 10% and 18%, but this is partially just due to their comparatively low cyclicality (which I’ll talk about in a second). In 2022, a stronger year, they would have done about 29%, pro rated for the merger - still better than competitors, who generally did 20-25%, but not as good as the calculations I showed above would suggest.

However, management are targeting 40% by 2028. Two things will help them to achieve this:

Housebuilding wind-down - the non-partnerships business dragged down ROCE in 2022 and 2023. Winding it down is expected to release £1 billion in total, significantly reducing capital employed

Synergies - versus 2022, the Countryside merger should result in £60m of cost savings (of which £50m already achieved) and the transition to pure-play partnerships should save another £25m

There is reason to believe they’ll achieve this target. Pre-covid, the partnerships businesses of Galliford Try and Countryside (i.e. the two components of modern-day Vistry’s partnerships business) earned ROCEs of around 50% and 80% respectively.

*Defined as adjusted EBIT / (tangible equity + net debt - net pension asset)

Acyclicality

Both the institutional investors who buy PRS and the housing associations who buy affordable are much less sensitive to the economic environment than the private home buyer. This is evident in 2023 results. Due to several factors, including the end of the Help to Buy scheme, the cost of living crisis and higher interest rates, most developers saw unit completions fall 20-35%. On the other hand, Vistry’s completions fell just 5%. Only a third of their business is exposed to the private market, and they were able to sell any homes that the private market didn’t want to their partners (in H1’24, with private market weakness continuing, they’ve ramped partner-funded up to 76%, more than making up for private).

This stability isn’t just nice because it means revenue and profits march in a straight(er) line upwards. It also reduces costs significantly. Contractors prefer longer-term contracts, which provide them more income stability (Fitzgerald says contractors know Vistry as “the developer that will pay their mortgage” - H1’24 call), and they’re willing to accept a somewhat lower hourly pay rate in return. And it goes without saying that materials are cheaper when you can order them in bulk, several months ahead. Vistry’s visibility of future build rates allows them to take advantage of this, while other developers are continually cutting and rehiring contractors, and putting in last-minute materials orders or cancellations.

Moat

40% ROCE, pretty much acyclical and with strong growth tailwinds - that’s a pretty attractive business to be in, meaning you’re going to need a strong moat to defend it. Housebuilding is usually a pretty moat-less industry, but I think there are some differences in the partnerships model - in particular mixed-tenure regenerations - that make this a completely different kettle of fish.

The key thing to understand is that councils are putting their reputations on the line with these projects. Housing developments are always a point of contention in local communities - especially for urban projects, and even more so when the project involves demolishing and replacing a still-inhabited block of council housing (as many brownfield regenerations do). See here, here and here for examples of people being rather angry about such projects. If the developers cock it up and it gets publicised, it could scupper the councillors’ chance of re-election.

And cock-ups are not rare. These are massively complex projects - not just technically, or in terms of managing the desires and concerns of the numerous parties involved (developer, HA, LA, PRS investor, community); but also in terms of social issues. Traditional housebuilders view affordable housing requirements as a burden, a cost to be minimised, so you often get redevelopments which leave only half as much social housing as they knocked down, or projects which cluster all the affordable units in the least desirable corner (even utilising separate entrances in order to, by the developer’s own admission, avoid affecting private property prices).

All of this incentivises councillors to be very risk-averse - perhaps even more than is economically justified. And how does a risk-averse LA select the safest possible partner for their big new project? Track record, quite simply. So it stands to reason that if there was one developer with by far the best track record (both in terms of size and success rate), they would be able to charge at the very least a few percent more than competitors with weaker records.

I’m sure you know where this is going - Vistry, or more accurately Countryside, is that developer. My conversations with industry analysts and management from both Vistry and other housebuilders confirmed this. But don’t take it from me, take it from one of their main competitors, Lovell, who are targeting an 8% margin and 25% ROCE compared to Vistry’s 12% and 40% targets. Or more emphatically from Bellway, who shut down their London Partnerships business last year, abandoning ongoing developments.

If that’s not enough, there are a couple of other elements that solidify Vistry’s moat:

PRS Relationships

PRS investors, similar to LAs, are highly risk-averse. As mentioned, these are most often pension, endowment, or sovereign wealth funds, for whom security of principal is much more important than maximising yield. If they have a developer that they’ve worked with multiple times in the past, who has delivered the units on time and to spec while being accommodating of their needs, it’s going to be quite hard to persuade them to take a gamble on a new partner.

Because the partnerships margins are so slim, this has an outsized effect on competitors. Let’s imagine a PRS investor who has such a relationship with Developer A is planning to buy some units at a price they expect to result in a 5% yield, and in order for the investor to take the risk of going with some Developer B instead, B would have to offer a 5.5% yield - seems reasonable to me. If A is making a 12% margin on that project, and both their cost bases are the same, B would have to deliver the project at a margin of just 3% to win the bid.

The risk to the PRS investors is not imaginary. Take, for example, this £800m deal that PRS investor Sigma signed with Keepmoat, for the delivery of 5000 homes over 5 years. The announcement of that deal in 2016 was followed by 2 years of radio silence (aside from this measly 24-home completion in late 2017) - then in 2018, Sigma suddenly announce an agreement with Countryside for 5000 homes… over 3 years. Earlier this year, Sigma signed for another 5000 homes with Vistry, calling them their “foundation partner”. Keepmoat was simply unable to keep up with the volumes demanded. My conversations with industry insiders suggest this is far from a one-off - no other developer is focusing on PRS like Vistry is.

Good Old Economies of Scale

When I gave the Developer A / Developer B example earlier, I assumed both cost bases are the same. Unfortunately for B, if Developer A is Vistry, that’s not likely to be the case. Vistry delivers several times more units per year than any of its partnerships competitors, inevitably leading to a lower cost base - in part because at a certain size it starts making sense to in-house the manufacturing of construction components (Vistry’s timber frame operation should be capable of producing 12,000 units’ worth by 2026). So not only are you going up against someone that your potential customer is willing to pay more for, you’re doing so with a meaningfully higher cost base.

Management

CEO & Chairman - Greg Fitzgerald

Greg is a very likeable guy. He’s from a working class background, having started in the housebuilding industry as a tea boy back in the 1970s; he’s got a good sense of humour, and he’s not afraid to speak his mind to analysts (see the H1’24 results meeting for evidence of both). But it’s important to set that aside, and take an objective look at his track record - here are my thoughts on that.

1. CEO of Galliford Try, 2005-2015

When Greg became CEO of Galliford in 2005, it derived three quarters of its £720m in revenue from construction contracting, though it was only the remaining quarter, housebuilding, that actually made them any money. Clearly, Greg recognised the issue there, because in 2007 they bought the housebuilder Linden homes for £270m in cash. This purchase was made at a P/E lower than Galliford’s own shares, and Linden was (and is) a well-regarded brand, so no issues from me there.

In 2008/9, the GFC came along.

In October 2009, right at the market bottom, Greg made a rather bold move - a £120m rights issue, raising more cash from existing shareholders (at a price where non-participation would be significantly dilutive) - with the proceeds used to buy a huge amount of land at bargain prices. With this, they announced plans to double the size of the housebuilding business by 2012 - which they ultimately succeeded in doing.

I do note, however, that despite 2013 being a year of continued recovery for the UK housebuilding industry, revenue was flat YOY for Vistry with completions down slightly. I wonder if they pulled some revenue/completions forwards in order to claim they hit the target.

The following 2 years saw pretty strong growth, driven in particular by their partnerships business, which had sort of been borne out of having housebuilding and contracting operations under the same roof. At the end of 2015, Greg retired as CEO, taking the chairman role, which he remained in for roughly a year. Overall, the company did well during the 11 years of his leadership. Shareholders who bought the day he became CEO, participated in the rights issue, reinvested dividends and sold the day he left achieved an AER of ~18%, despite having bought in during a fairly euphoric period.

However, I do have a couple of concerns:

Over his tenure, the contracting unit made a total profit of approximately zero. In hindsight, the sensible thing to do would have been to sell as soon as possible and focus on the development business.

While Greg was with the company, Galliford continually used the majority of FCF to pay dividends. However, the stock remained at a pretty cheap multiple throughout, implying buybacks would have been a better use of cash. Also, the business averaged a ROCE of ~15% throughout, which suggests reinvesting the cash may have been even better (though it may be that they were only able to reinvest a limited amount at those levels - diminishing returns and so on).

2. Bovis Homes Rescue, 2017-2019

Financially, Bovis were still doing decently when Greg joined, having earned a 15% EBIT margin in the last FY. But reputational damage compounds over time - this would fall to 12.4% in FY17.

Fitzgerald didn’t waste any time - legal, planning, design and engineering were all outsourced or partially outsourced, and the effect was pretty immediate - the HBF rating jumped to 4 stars for 2017/18. The financial effect was positive too - EBIT margin rose to 16.4% in FY18. In 2018/19 they regained a 5-star rating, and FY19 saw further revenue growth and margin improvement. They even began building a partnerships business - the man likes partnerships, I guess.

3. Bovis Homes buys Galliford Try

Galliford had suffered somewhat over the 2 years since Greg left - partially due to the contract cost problems I mentioned, but also due to weakness in Linden Homes. Partnerships, incidentally, was doing excellently, but being a lower-margin business this was overshadowed, and altogether the stock halved between 2017 (when, ironically, Galliford made a failed pass at Bovis) and 2019.

Taking advantage of this temporary weakness, Greg made an offer for Galliford’s housebuilding and partnerships businesses - paying £1.075b for £200m of EBIT. Considering they got the high-quality partnerships business, and achieved an additional £44m P.A in synergies, this was a pretty phenomenal deal for Bovis shareholders.

My only criticism is that Bovis paid primarily (~75%) using its shares, which were pretty cheap at the time. Share count expanded 57%, implying a valuation for Bovis - which was doing ~£180m before tax - at about £1.45b. Paying with equity would only really be justifiable in that scenario if (a) Bovis already had a fairly leveraged balance sheet, or (b) borrowing rates were very high. But Bovis had a net cash position and, based on the rates they and other housebuilders were paying at the time, probably would’ve been able to fund the acquisition at about a 5% interest rate. If they had done so, EPS would have expanded (ceteris paribus) 80%, instead of 35%.

4. Vistry buys Countryside

In September 2022, Vistry had a market cap of ~£1.6 billion, and Countryside ~£1.15b. Vistry offered £1.27b for Countryside, which strikes me as an unusually small premium (~10%), considering that (a) Countryside had been valued at ~£2.5b just a year prior, and (b) Vistry expected to be achieve £50m of synergies from the merger, which alone is probably worth £500m. What I’ve heard from major Vistry shareholders (who were previously Countryside shareholders) indicates two reasons they accepted this deal:

Vistry were paying mainly in shares (again, ~75%) - the shareholders thought Vistry was also undervalued at the time, so really they’d be receiving more than £1.27b in underlying value (and they’d benefit from the cost synergies)

They liked Fitzgerald a lot, and saw him as one of the only people that recognised the true value of the partnerships business (and knew how to run it)

Did Vistry shareholders actually benefit from this acquisition? Well, Countryside Partnerships had done £108m in adjusted EBIT in 2021 (don’t worry, they’re rational adjustments), and was in the process of winding down the non-partnerships business - a move they expected to release another £415m. This would put the EV/EBIT at about 8, net of capital release. However, Vistry was only at 7.5x, so Vistry shareholders were relying on the realisation of that £50m of synergies (which would reduce the effective multiple to 5.4x) for the merger to be EPS-accretive. Fortunately, they ended up achieving £60m. It’s also worth noting that EPS doesn’t tell the whole story - Countryside Partnerships is a higher-quality business. So yes, Vistry’s shareholders did benefit.

Other Management

CFO - Tim Lawlor

Tim was previously CFO of Countryside, and became the CFO of Vistry when the two merged in November 2022. Prior to Countryside, he had held CFO roles going back to 2002, and has a Master’s in economics from Cambridge (big up).

He and Greg share the time fairly evenly on earnings calls. There isn’t a huge amount to report from those - he comes across as competent, and a bit more serious than Greg.

COO - Earl Sibley

Earl was CFO of Vistry/Bovis prior to the Countryside acquisition, a position he had held since 2015 (and from 2006-2008). When Bovis’s then-CEO Dave Ritchie stepped down during the crisis in late 2016, Earl briefly took the reins as interim CEO, before Fitzgerald joined. Based on how quickly the quality issues began reversing, I’d infer he was doing something right.

Between 2008-2015, he was a finance director at Barratt, and prior to 2006 he spent 13 years as a senior manager at EY. I have no strong personal impression of him.

Partnerships CEO - Stephen Teagle

Stephen joined Galliford Try in 2006 and was appointed CEO of its partnerships business in 2016, remaining at the head when it was merged with Countryside partnerships in 2022.

Executive Compensation

Compensation is relatively generous for a UK company, but not excessive. Target comp for Greg is £3.3m, with a max of £5.7m; Earl and Tim together is roughly the same. Non-executive directors, with one exception, are paid £28-70k. Personally, I’m a fan of low director fees - an “independent” director whose main source of funds is their £200k director’s fee is not really independent in the slightest, and will inevitably bend to the CEO’s will.

Around 70% of compensation is variable for the three top execs, and I think it’s weighted quite sensibly - about half of it is based on earnings, another quarter on capital employed or ROCE (encouraging management to return capital to shareholders when the return they can achieve on reinvestment is not attractive) and the remainder on TSR, net debt and a small amount on ESG metrics.

Cost Understatements

On October 8th, 2024, Vistry announced full-life costs on 9 of its ~300 developments had been understated by about 10%, with a total impact of £115m (to be recognised over the next 3 years). They explained the issues were all within just one of their six divisions (South), and the management responsible is being removed, but this did little to calm the market - from around £13 pre-announcement, the stock plummeted to ~£9.60.

Subsequently, Vistry announced they were bringing in an external auditor to conduct an independent, in-depth forensic review of all 300 sites. The audit found a couple more developments - also in the South division - with similar problems, resulting in an extra £50m impact. Shares fell further to below £7, before ending the day at £7.38.

Sell-side price targets have chased (or possibly led) the stock down, voicing concern that this may be symptomatic of fundamental profitability issues in the partnerships model. Interestingly, several of their reports indicate this was a fairly widely-held concern among the sell-side even prior to this debacle - which I find rather strange considering the excellent performance delivered by both Countryside and Galliford Try’s partnerships businesses in the past.

Out of the many sell-side reports I read, only one of them mentioned the fact that the issues were almost entirely on legacy housebuilding sites, not partnerships. This seems to me like pretty key information. However, even when this was announced publicly more recently, the stock didn’t seem to care.

Why did this happen?

The independent review found the problems were principally due to “insufficient management capability, non-compliant commercial forecasting processes and poor divisional culture” - in other words, shitty mid-level management. Vistry notes - somewhat pointedly - that South is the only division whose management consists entirely of people from the Housebuilding side.

The cost estimates would have been carried out several years ago, then not updated in the face of high build cost inflation. That’s not to say this was an accident - the problems were sufficiently obvious that they became apparent as soon as regional managers started reporting directly to the CFO instead of the divisional manager (a change made shortly before the announcement).

I’m still left with a lot of questions. Who hired these managers? Did they come from Linden or Bovis? What motivated them to hide these mounting problems - is there toxicity above them or were they just trying to hold onto their bonuses? How did they get away with it for so long?

I will update this post if any of this information comes to light, but I doubt it will. At current prices, this is uncertainty I’m willing to bear.

Reassurances

The external auditor found no similar problems - financial, cultural, or in reporting standards - at other divisions.

Insiders have been buying - on the day of the first announcement, Greg bought £200k in shares (not something he usually does) and two independent directors who had never purchased shares before bought £75k and £40k respectively. Browning West LP, Vistry’s largest shareholders (with a seat on the board) purchased an additional £7.5m, and after the most recent announcement, bought a further £3.5m.

The market, judging both by the content of sell-side reports and by the price action, has treated this as if it represents a fundamental, long-term issue in their ‘untested’ core business model, when in fact the problem was concentrated in their legacy business in wind-down.

The majority of the cost will be recognised in FY24, and will reduce pre-tax profit by about a third - yet the price has fallen a full 43%. If we assume the market at least tries to price stocks based on intrinsic value (arguably a rather fallible assumption nowadays), the market is essentially saying it expects cash flows to be permanently impaired by 43%, despite the fact that even when several years’ worth of accruing cost overruns are recognised mostly in a single year, it reduces profit by only a third!

The independent review found that top-level management took prompt and robust action upon discovering the problems. My conversations with shareholders have indicated management became aware on October 4th, only 4 days prior to the announcement. There was zero attempt at a cover-up here.

Valuation

As usual, I will not conduct a full DCF as I don’t think it provides any value. Instead, I’ll give the key numbers which I believe make it obvious the business is undervalued, and I’ll indicate the range I believe intrinsic value likely lies within.

First things first, let’s get a normalised earnings number.

EBIT: In 2023, adjusted operating income was £488m. H1’24 was £20m up on the prior year - I think because activity has slowed somewhat in the South division, and the market as a whole has weakened slightly (see Barratt, Persimmon, Bellway stocks), H2 will probably down slightly before exceptionals, putting us at about £500m

Interest: Net interest expense was £81m in 2023, and the most recent analyst call implied it would be about the same again - we’ll say £85m. That puts 2024 adjusted pre-tax earnings at £415m, versus the £430m guided for, which feels about right given the environment.

Exceptionals: I often see people completely disregarding nonrecurring costs/losses in their valuations, which grinds my gears. Most “one-off” costs, like inventory impairments or restructuring charges, happen at least every few years - you will systematically overstate profits if you ignore them. Obviously, amortisation of acquired intangibles can be ignored, as can genuinely exceptional costs after a major acquisition.

I examined the past 10 years of financials for Vistry and its predecessors, and found £300m of non-exceptional “exceptional” costs, on £33b of revenue. Based on expected 2024 revenue, that would imply £40m of exceptionals P.A. - that’s fairly hefty, and I think higher than most analysts would put it, but I’m all for conservatism.

Tax: The statutory corporate tax rate is 25%, and property developers pay an extra 4% - so they should be paying 29%.

Capex: Usually we would consider the difference between capex and depreciation, but both charges are pretty tiny for property developers, so we will just take depreciation at face value.

This leaves us with a normalised earnings power of £266m.

Next, an adjusted market cap.

As I write this, the market cap is £2.51b. Management were expecting the wind-down of the housebuilding business to allow for £1 billion to be returned to shareholders, via buybacks and special dividends, in FY24, 25 and 26*. As mentioned, around £200m has already been returned. However, on the most recent call, it was indicated that they’re expecting it to take a little longer than expected to return the remaining amount. In order to be conservative, I’m going to assume they only manage to return another £600m; and that it occurs in equal instalments over 2025, 2026 and 2027. At a 10% discount rate, the present value of that is £515m. That takes us nicely down to an effective market cap of £2.00b.

Hence, the economic P/E multiple we’re paying is about 7.4. The maths is a tad rough, but valuation is as much an art as a science - it will do.

*Side note - on the most recent call, with the stock down almost 50% in just a month, an analyst asked why they haven’t suspended the share buyback programme given the issues found. Hilarious. Analysts don’t just like to buy high and sell low (see JPM recommendation chart below) - they’re asking management to do the same! Greg responded that they’re looking at ramping it up instead, given today’s prices - music to my ears.

The Future

Of course, the current level of earnings is only half of the story - it matters immensely the rate at which those earnings will grow (or possibly shrink) over time.

Earlier this year, management revealed a set of “medium-term” (2028, it seems) targets. Aside from the £1 billion returned to shareholders, these included a 40% ROCE and £800m in operating income at a 12% margin (implying £6.7b revenue - a 10.5% CAGR from 2023). Due to the cost problems and broader weakness in the housing market, that’s now expected to take slightly longer - they haven’t put a year on it yet.

The thing is, 10.5% is not a particularly aggressive assumption when compared to Labour’s goals. I suggested earlier that 32,000 homes in 2028 might not be a completely unreasonable number if the funding is there (if Labour’s targets are met, that would actually represent a material reduction in market share) - and that would imply a 15% CAGR just on the unit side.

Truth is, I don’t have a good idea of what the next 5 years’ growth will look like. In large part, it depends on (a) how well the overall UK economy performs and (b) how aggressive the government is with housing, in particular:

The 2026-2031 Affordable Homes Programme budget, which will probably be announced in spring 2025

The next social housing rent policy - currently, social rent increases by CPI + 1% each year, in 5 year periods (at the end of which the rate is reassessed to compare to local rents and incomes). Housing associations are currently in conversation with the government, pushing for it to be fixed at CPI + 1% for a 10-year period instead - the extra security would substantially increase their willingness to develop social housing.

I think it’s usually a bad idea to expect a higher growth rate than management is expecting. I also think it’s unlikely we see unit growth any lower than 5% per year. This leads me to a growth range of 5-10% annually over the next 5 years. Importantly, growth seems likely to continue well after the next 5 years.

Okay, where does that leave us? £272m earnings, high-single-digits mid-term growth (at a high ROCE, importantly - most of their cash flows will be distributable over this time. If you growth 10% a year with a 40% ROCE, you can pay out three quarters of your earnings), with a strong moat, pretty decent management and the potential for some margin expansion. I would say intuitively that’s worth somewhere between £4.5b and £6b.

A reverse DCF is a good tool for a sanity check - at a 10% discount rate, £4.5b could imply 5Y growth of 5%, and terminal growth of 3.3%; and £6b could imply 10% then 4%. Those seem like some pretty reasonable assumptions.

Add that £515m PV of distributions and divide by 332 million shares, and we get a fair value per share of £15-20, meaning the current share price of £7.56 represents a 50-62% margin of safety. Given that this is a pretty stable business in a stable (despite what headlines might lead one to believe) economy, that’s good enough for me.

Risks and Concerns

While I think the risk/reward looks rather attractive here, this is not a lay-up. There are a couple potential concerns I want to briefly highlight (as much for posterity as anything).

What if costs problems are more serious than I realise? This is the big one, obviously - it seems to be the main area where myself and Mr. Market disagree. One of the things that’s bugging me is that Vistry aren’t disclosing who did their audit - they’ve just said it was “one of the larger accounting firms”. Their rationale is that this would have meant more 2 more weeks of jumping through hoops before the audit could actually get underway, and they wanted the results as quickly as possible. This seems plausible - presumably a firm would insist on more verification steps and general bureaucracy if their name is being attached to a public report versus if it’s just an internal report. But still, there’s a nagging voice in my head saying that’s awfully convenient - what if this is a big cover-up and it’s way worse than we realise?

I take solace in the numbers. For a worst case scenario, let’s say all £165m was accumulated over just 2 years; and that this was not one-off but ongoing and structural, such that their pre-tax income in the future is permanently reduced by £82.5m per year. Bad as it sounds, that would only slim their underlying earnings by 22% - far less than the drop that resulted from the announcement, and not even enough to put the effective P/E above 10 (talk about a margin of safety).

I’m not crazy about management. It goes without saying that cost understatements of this magnitude just shouldn’t happen at a business this size. Additionally, I don’t think Greg has always made the most value-accretive capital allocation decisions in the past (as discussed), and I think their compensation is higher than I’d ideally like. Finally, I would have liked to see heavier insider buying from top management after the recent news - Greg’s £200k buy only increased his shareholding by c. 1%. But who knows, maybe he just doesn’t have the cash on hand. Finally, I noticed

I do note that certain major investors who know the business and team a hell of a lot better than I do are very keen on Fitzgerald and his team, so I may be reading too far into things.

Mitigants

I’m not usually a fan of the ‘superinvestor portfolio’ stuff, but I do think Vistry has some rather encouraging shareholders:

Abrams Capital (3% of shares) - David Abrams is a value investor that I massively respect - he keeps a low profile so you most likely haven’t heard of him, however he’s thought to have returned ~15% a year since 1999, which is one of the best track records I’ve seen from a value investor over this period. I came across him from this Value Investing with Legends podcast episode (Ctrl+F “Abrams”), finding myself agreeing with just about every word he said.

Browning West (10% of shares) - run by a guy called Usman Nabi, who also sits on the board. I hadn’t heard of these guys before and don’t know what their performance is like, but they’re concentrated fundamental value investors (as well as activists), which is just what I want to hear; and Vistry is probably their largest holding (15-20% allocation, and a lot more pre-crash). It is reassuring to know Usman will be advocating for the shareholders in every board meeting, in case Greg’s own £20m in shares isn’t enough.

David Capital Partners (3% of shares) - yet another long-term value-oriented investor. The founder and PM, Adam Patinkin, was recently featured on the Graham and Doddsville newsletter, where he talks, among other things, about Vistry - unsurprisingly, since it was seemingly over half of their portfolio at the time (I use the past tense only because I don’t know how their AUM has changed).

I’m under no illusion that having these guys on board eliminates the risk or guarantees a good return. At the end of the day, risk is a fundamental part of investing, and the goal of sound investment strategy is not to eliminate it but to recognise, understand and manage it - and make sure you’re adequately compensated for bearing it. In this case, I feel that I am.

If you found this post useful or interesting, subscribe below to receive future posts straight to your inbox; or share with someone that might find it useful. Cheers!

50x1.13^6 + 50x1.13^4.5 + 150x1.13^0.5 - 350 ≈ 0.

50x1.18^6 + 50x1.18^4.5 + 150x1.18^0.5 - 315x1.18^1.5 ≈ 0

50x1.29^4.5 + 50x1.29^3 + 150x1.29^0.75 - 305x1.31^1.5 ≈ 0.

50x1.49^4.5 + 50x1.49^3 + 150x1.49^0.75 - 305x1.49^1.5 + 150x1.49^0.75 - 175x1.49^1.5 ≈ 0.

I just thought I’d chime in and echo the appreciation of your analysis. Something I wish I had the time to research but with young kids every second is precious.

I popped this on my watchlist after the first profit warning and was reluctant to buy in due to the inevitably of a second PW. With the second warning out I feel the risk reward has started to become more appealing. South division aside, I particularly like the additional £8m cost issue disclosures, the reduction in completions and the downward revisions of PBT. Those items make me feel that the new forecasts are achievable -perhaps beatable if I’m being incredibly optimistic.

I completely agree that there seems to be a lot of criticism of the partnerships model however it doesn’t seem to be the cause of this issue, more likely poor estimating, cost reporting, mismanagement and perhaps a smidge of legacy brushing under the carpet. The criticism centres on inflationary pressures including the ENI contributions which seem relatively muted inputs from high level analysis I’ve conducted. I’m not sure if these commentators give enough weight to the fact that we’ve recently come through a period of unprecedented inflation and legislative change in the removal of rebated diesel use on construction sites. Short of another energy crisis it is likely that inflationary inputs will pale in comparison over the next few years. Simply stated any company that has come through the last few years with limited debt/ fundraising has demonstrated a resilience that makes me very comfortable. In addition it is front and centre of construction managers decision making and certainly more prevalent than it was pre 2020.

On a cautious note: one thing I’ll be keeping a close eye on is monthly and daily net debt as it would be reasonable to assume that as the partnerships model up front cash starts to come through the numbers that this figure will reduce -perhaps even dramatically.

These reasons, asset backing, shareholder returns along with many of the additional reasons for optimism (better researched and explained by you) are why I have taken a position and kept buying through the recent lows, I also like the idea that house builders should be relatively shielded from Trumps antics across the pond.

Labour have promised to catalyse house building and while it is apparent that it won’t trend close to their pre-election grandiosity, Vistry will most likely be swimming with the current all they now need to do is execute and under promise then over deliver for the next few reporting updates.

Great report!!! 👏🏼